In Sardinia, there has always been a manic obsession with death.

Thousands of years ago, Nuragic tombs were so imposing not to house giants, as their evocative name suggests, but because they likely served a function beyond mere burial. The living never severed the thread that connected them to their deceased ancestors, perhaps seeking protection or answers. It is believed that Sardinia also practiced incubation, a ritual widespread in the ancient world, in which people slept in burial sites either for therapeutic purposes or to seek guidance from the dead. Tertullian reports that even Aristotle mentioned a Sardinian hero capable of freeing those who slept in his sanctuary from disturbing visions, thus highlighting the existence of a ritual sleep practice connected to the dead.

Even today, the obsession with death remains deeply ingrained in Sardinians, who struggle to detach themselves from their past.

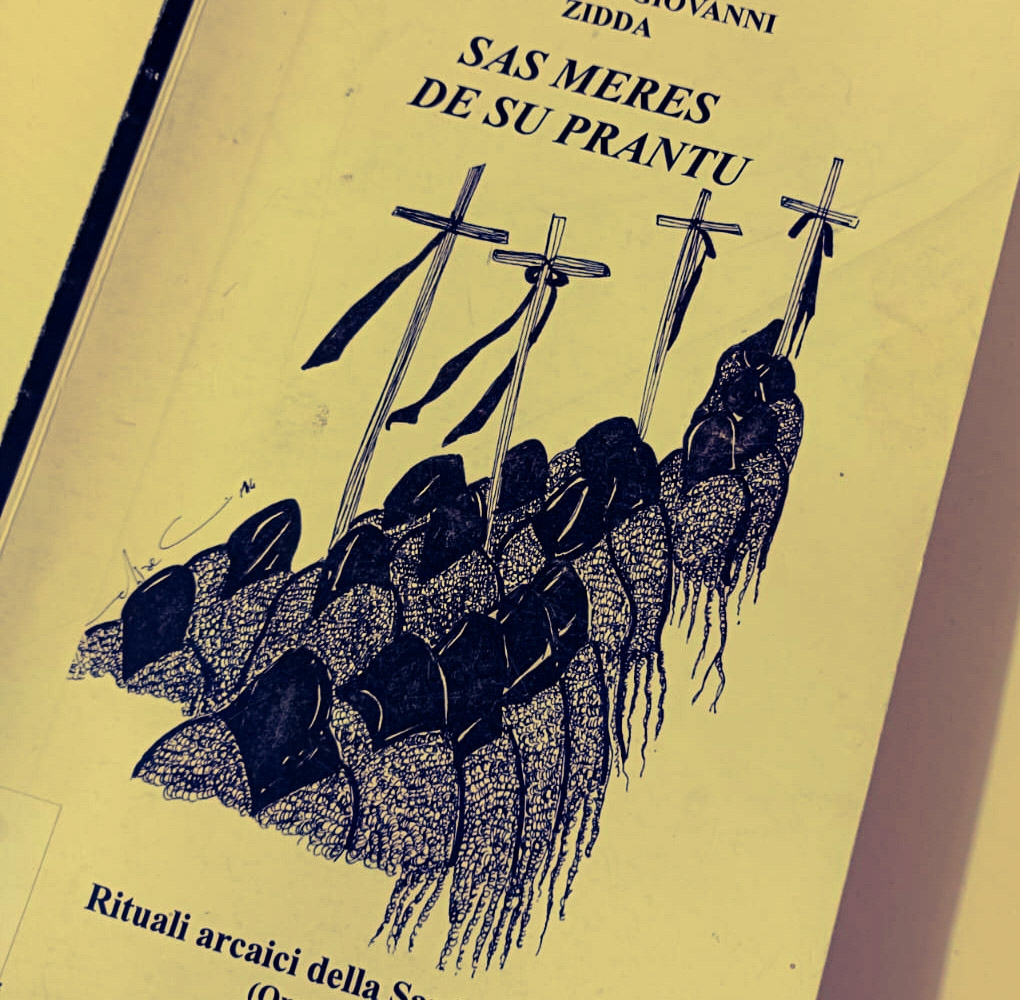

In Sardinia, the past has always been an open wound, and like any open wound, it is disinfected, treated, and given particular attention. If the Nuragic people slept near the houses of the dead, practicing incubation to seek answers, today it is the dead who have entered the homes of the living to remain with them: people fear the dead, they make donations in their honor, women dress in black for life, they mourn them with funeral laments called attitos, and they observe long and solemn collective vigils and rituals. In villages, when entering a home, one often finds themselves surrounded by more photographs of the deceased than of the living. Cemeteries are better maintained than churches, and when something is donated, it is done saying “a sas animas”—for the souls.

Observing this peculiarity closely suggests that, perhaps, behind this obsession lies a true metaphor—a way of perceiving the past, metaphorically embodied by death. Sardinians have a deeply conflicted way of intertwining past, present, and future. Change has always been seen as a threat: through invasions, colonization, and forced emigration. For this reason, a static self-image was the only certainty to cling to: what has been, su connottu (the known), is perceived as the only way to preserve identity. But remaining still while everything moves is a true form of self-destruction because, as Tancredi says in the masterpiece The Leopard, “If we want everything to stay as it is, everything must change.”

This tendency towards immobility is still present in every sphere today, from politics to culture: there is a constant tension between the past and the desire for progress, which never materializes for fear of losing one’s roots.

Remaining suspended between life and death, between memory and nostalgia, between identity and the fear of losing it, has led to an eternal state of liminality that, in the long run, is inevitably destructive. This liminal state forces Sardinians to live between two worlds: it prevents progress, yet, being static and confused, it does not even fully embrace the richness of the past, which has long been dying.

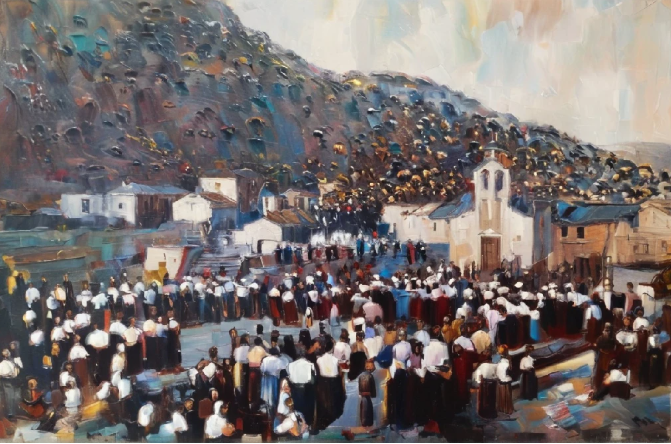

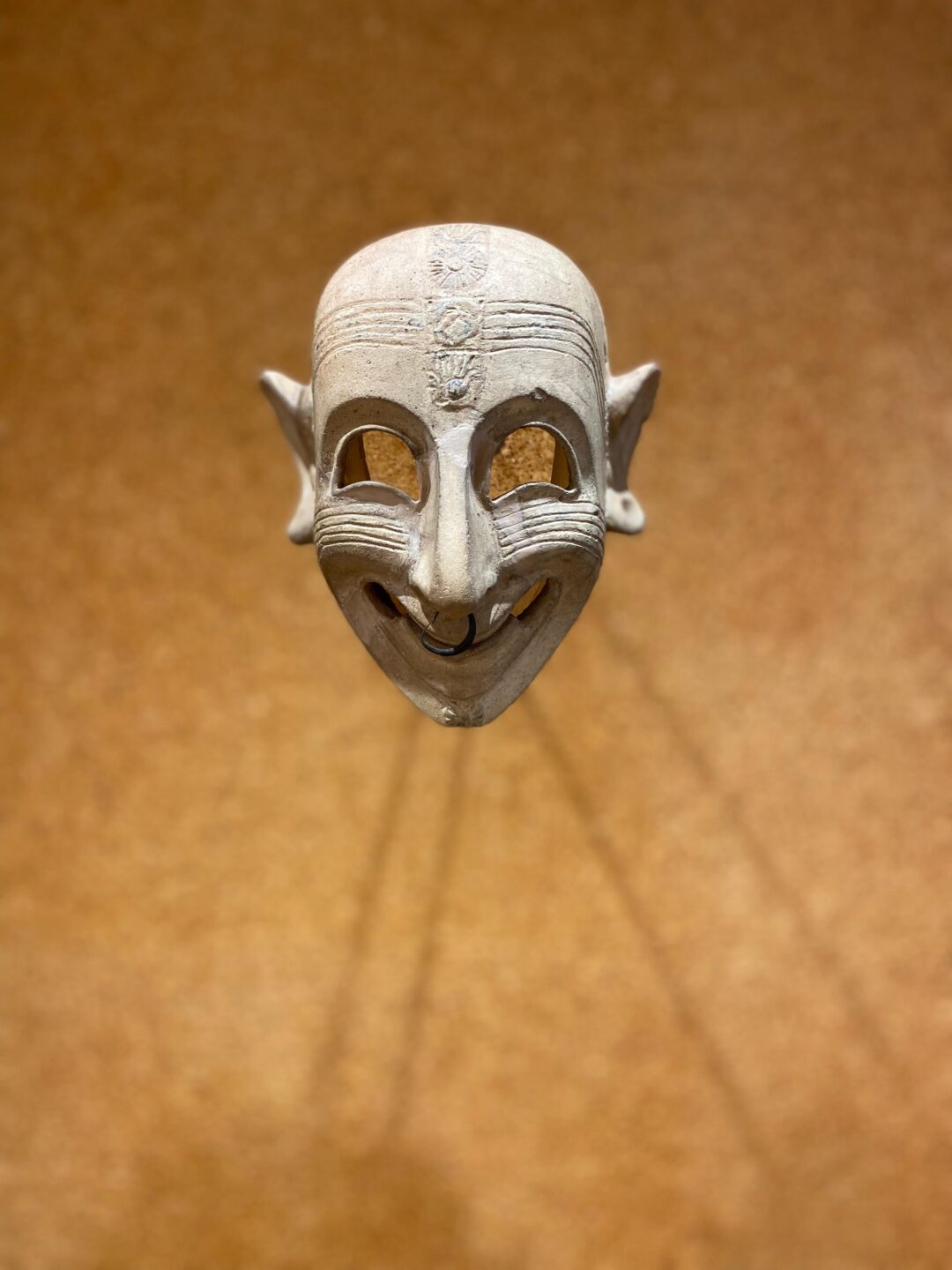

For this reason, now that authentic Sardinian culture is slowly fading, numerous cultural associations are almost neurotically trying to keep it alive, paradoxically achieving the opposite effect: promoting folklore instead of culture. Folklore, unfortunately, has become a product to be consumed—a static image of what once was but is no longer authentic because it is no longer an integral part of daily life.

Cultural conservation efforts that aim to preserve tradition often end up stripping it of its deeper meaning, turning it into a folkloristic postcard to sell to tourists. When something is turned into a museum exhibit, it loses its authenticity and becomes reproducible, commodified.

Sardinia is an island living among the ashes of its memory, surrounded by its own ghosts, still dressed in mourning—like a widow.