Art.1 – The offense must be avenged.

A man who evades the duty of vengeance is not a man of honor, except in cases where, having proven his virility throughout his life, he renounces it for a higher moral reason. (Antonio Pigliaru, The Code of Barbaricinian Vendetta)

In Sardinian, the word homine does not merely indicate a man in the biological sense; it signifies a strong, skilled man, capable of mastering challenges through his abilities and aggressiveness. A man capable of commanding respect, of being virtuous. A man capable of being a balente.

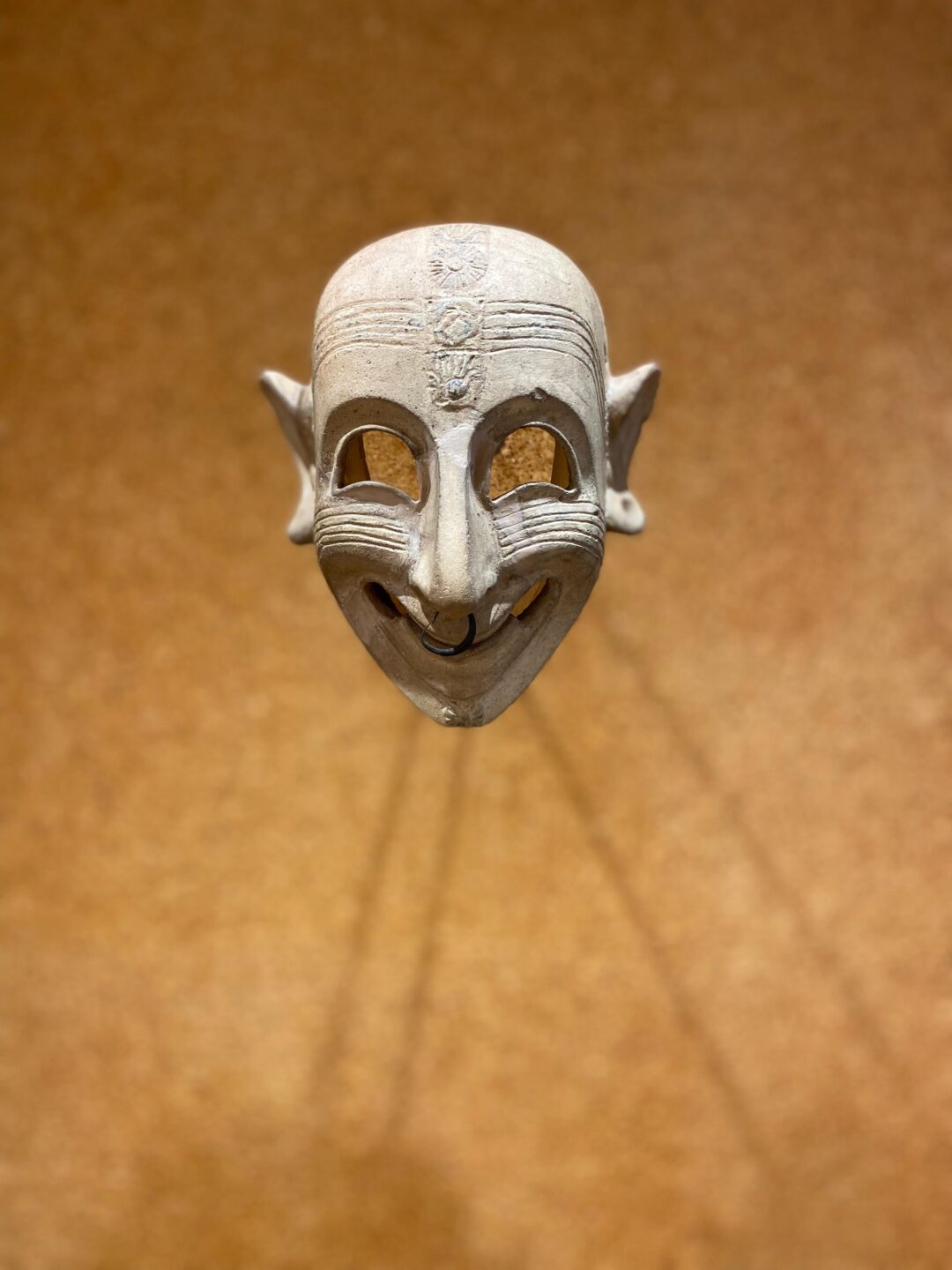

In the past, the Sardinian Barbaricinian shepherd, s’homine balente, was the undisputed protagonist of an isolated reality, more incredible than unique within Sardinia: the Barbagia. Pastoral, mountainous, harsh. An island within an island, with its own code, known precisely as the Code of Barbaricinian Vendetta. The exact time and manner of its origin are unknown, but it is known to be ancient, likely predating the Roman era.

Although today it carries almost entirely negative connotations, in Barbagia, vengeance once played a crucial role: ensuring social balance in the absence of a reliable and adequate state authority.

Pairing vengeance with social balance may seem contradictory. But that’s exactly how it worked: since state justice was ineffective (as often happens even today) and was entirely alien and hostile to the rules of the Sardinian pastoral world, each individual had the duty to seek justice for himself, both to ensure that social relations adhered to a shared set of rules that provided a stable structure to a world that would otherwise collapse, and to demonstrate to the community that he was not weak.

If a shepherd showed weakness, he lost credibility (his so-called honor), and both he and his family risked further offenses. This is how this world raised strong, vengeful, and highly responsible children (my grandfather, at seven years old, already slept alone in the countryside to guard the flock, which would have been stolen in his absence). Likewise, women grew up strong and intimidating. In a harsh region like Barbagia, the goal of raising skilled and strong individuals was not to dominate others but to be someone who could be relied upon, to be a stable piece in an active social network, in a pastoral world where loneliness and the challenges of nature were formidable obstacles. Obstacles that only a balente could face.

It is essential to emphasize that Barbaricinian vendetta was not an impulsive or chaotic act, like vengeance within criminal organizations, but a mandatory and predictable behavior, with clearly defined boundaries—a regulated act governed by precise social norms shared by all. If someone stole your flock, you could not respond with murder. A murder, in turn, was repaid with another murder of equal measure, not with indiscriminate slaughter. In some cases, a mediator intervened to prevent bloodshed. Women, children, and innocents were untouchable: vengeance struck only those directly involved in the conflict.

Every member of the community shared these rules, which is why this code, paradoxically, prevented chaos and, even more paradoxically, limited indiscriminate violence (unlike, for example, the mafia). More importantly, it ensured that no one abused power, because in a world of balentes, where everyone avenged themselves, before wronging someone, one thought twice (or even three times).

No one ever put this code in writing; it was orally passed down for centuries (hence, it was also called the unwritten code). That is, until 1959, when Antonio Pigliaru decided to formally document a true legal system based on Barbaricinian vendetta: a list of 26 articles that precisely outline the soul of the pastoral Barbaricinian society.

My grandfather, himself a shepherd for 88 years, had never read Pigliaru’s book. But when I asked him what he would do if someone stole his flock, he answered exactly as he was supposed to:

“Ma sì mi urana sa roba, non bi ando a caserma a los dennunziare. Bi la uro jeo puru.”

(“If they steal my flock, I certainly won’t go to the station to report it. I’ll steal it back myself.”)

It is clear that this code clashes with state laws. However, it is important to note that Sardinian banditry was not a direct product of the Codice Barbaricino but rather an offshoot of it. The laws of the Sardinian pastoral community clashed with those of the State, which, unable to understand them, never succeeded in offering a truly effective alternative model (in other words, “non nde achene, e non nde dassan fachere”-“they neither do, nor let others do”).

But today, where has this cascade of rules and certainties gone?

Today, only scattered and confused fragments of the Codice Barbaricino remain. Residual, disorganized remnants.

The coherence that once regulated the community has vanished, leaving behind only a thin layer of dust, settling—not by chance—in the harshest regions of the island.

In many areas of the interior, there are still groups of young and old who, following the distant (indeed, extremely distant) myth of the homine balente, represent a confused resistance. The fact that they resist is good, but the fact that they are confused is less so: they mimic defiance against the law, against the Carabinieri and the police, behaving as outlaws in a random manner—firing shots at festivals, getting involved in drug trafficking, brandishing knives over a wrong glance—without truly understanding why. The most courageous among them still harbor the instinct to challenge the rules of the State, but they don’t really know what they are fighting against. It is an innate (and, admittedly, understandable) distrust of the State and all its branches, inherited without unfortunately understanding its roots.

I say “unfortunately” because resistance, if well-directed, is a positive force. But resisting without understanding the reason, spreading confused and fragmented messages, traps us in the same prison we have always locked ourselves in out of necessity: stubbornly refusing to learn from the past while also failing to open ourselves to the present, remaining, therefore, mere observers of reality’s shadows, without ever truly becoming part of it.

Instead, history should serve precisely this purpose: to help us understand who we are and to teach us how to resist with clarity.