The true name of the fox in Sardinia is never spoken because it is not known. Instead, nicknames and circumlocutions are used, words that may seem like names but actually serve the opposite purpose: they help avoid naming it directly.

Marzàne, Macciòni, Giommarìa, Zusèppe rùbiu, Cùdda bèstia, Sa bòna ùcca, Fraìssu, once again, language is not only a tool for communication but also a filter through which humans perceive the world.

In Sardinia, the fox is seen with a mix of anger, respect, and fear. There is even a belief that saying its true name could summon its presence or invoke its power.

In Lodè, its nickname is Mariàne. The rivalry between humans and this animal became so intense that a special trap was created just to catch it: sa matzonera. In some villages, the fox is called Mazzòni, possibly referring to its thick, bushy tail (màzzu = bundle).

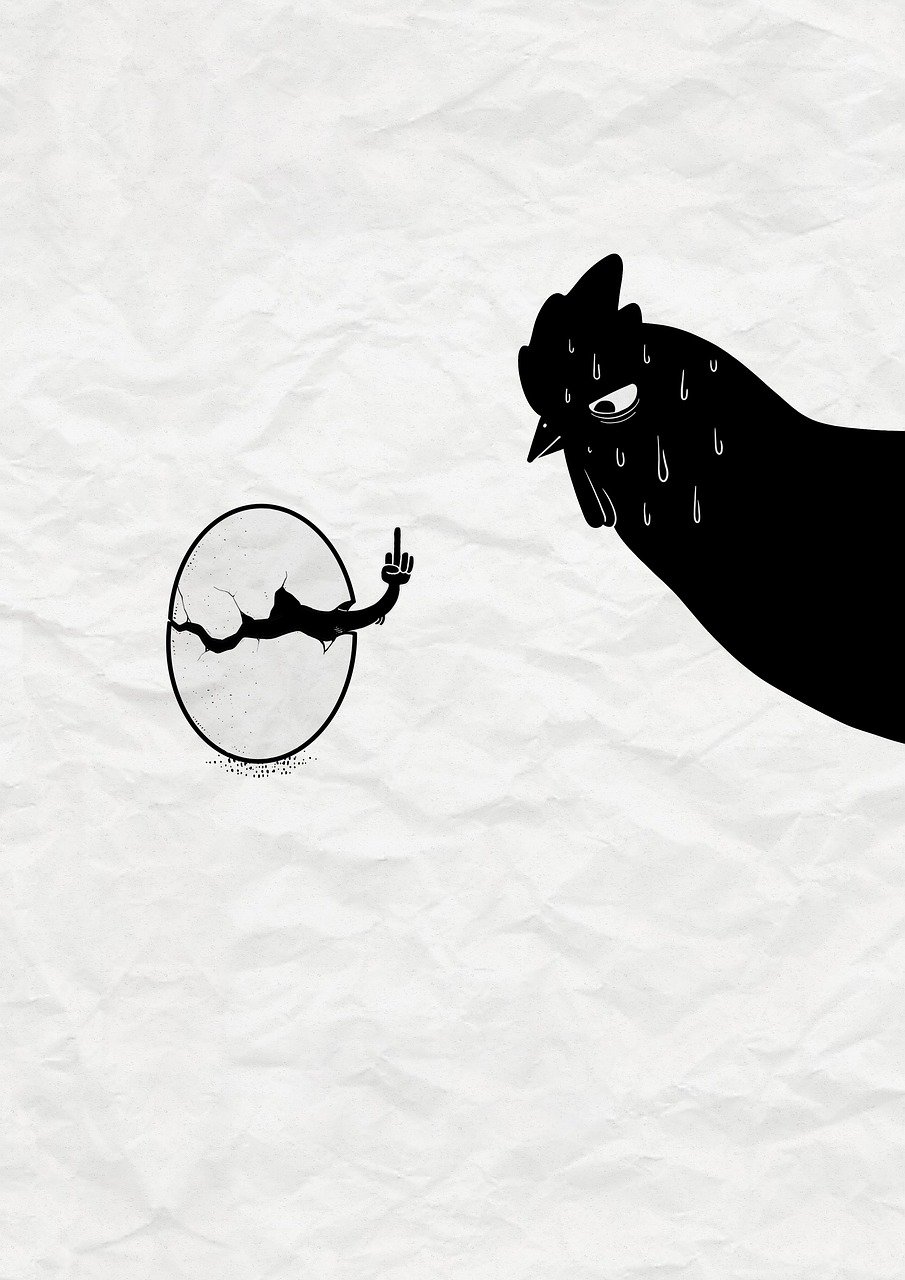

Once, my grandfather set up sa matzonera perfectly. The next morning, he discovered that he had caught a fox. He had captured it, yes, but to avoid being trapped, the fox gnawed off its own leg and escaped. Incredulous, my grandfather found only its bloody limb instead of the whole animal.

For me, this story is an incredible metaphor that naturally leads to a reflection on freedom and rebellion.

Sardinians’ hatred toward the fox, justified by practical reasons, since it killed sheep and chickens, also hides, in my opinion, a much deeper symbolic motivation: the fox represents cunning, freedom, and the ability to escape imposed rules.

Humans have always viewed with suspicion those who elude control, those who refuse to be subdued. Instead of confronting someone more cunning, they often prefer to eliminate them as a mere inconvenience.

When hunting in Sardinia, the fox is so clever that it literally tricks the hunters. It runs in circles, creating an illusion, while the hunting dogs, fooled by its scent, keep chasing it endlessly, thinking it’s a wild boar. When the hunters finally realize the deception, they exclaim, “Los iuket Mariàne” -“We’ve been played by the fox.”

Because the fox has repeatedly outwitted Sardinians, they developed an irrational hatred toward it, choosing to persecute it rather than outsmart it.

In everyday life, we see countless examples of how those who escape control and refuse to submit are viewed with suspicion and, eventually, persecuted: intellectuals and TV programs censored for criticizing power, journalists murdered or discredited for exposing the truth, honest politicians (though rare) sacrificed simply for daring to be honest, an act of true rebellion today.

But if the fox’s gnawed-off leg represents rebellion, and the three-legged fox limping away becomes a symbol of freedom, we must ask ourselves: how far are we willing to go to avoid being trapped?

The fox that gnaws off its own leg is a symbol of those who choose freedom at any cost. But what happens when power seeks to eliminate those who escape its rules?

A fitting mythological parallel is the story of the Teumessian fox. In Greek mythology, this fox was impossible to catch. One day, however, it was chased by a “magical” dog, Laelaps, which, in turn, never failed in a hunt. This created an unsolvable paradox: if the fox could never be caught and the dog could never fail, what was to be done? Let them chase each other forever, like Sardinian hunting dogs running in circles after the fox?

To break this infinite loop, Zeus turned both animals into stone.

The universal truth hidden in this story is that the battle between oppressors and rebels often leads to a dead end, destroying both sides. Power does not tolerate those who escape control, and those who rebel risk being annihilated.

But in the end, power may petrify rebels, yet the desire for freedom will always resurface in those who carry it in their veins, like an endless cycle.