Leaving takes you far away, but sometimes the real distance shows when you try to return to the place you left.

Coming back and speaking with a different grammar, seeing things with different eyes , apparently the same body, the same gaze, but changed.

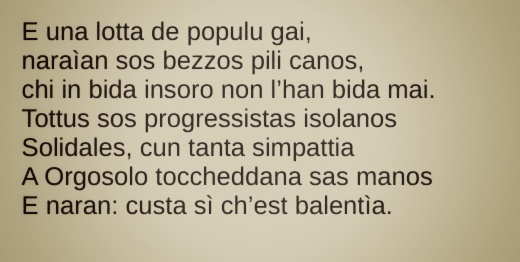

In the past, many people emigrated from the small villages of central Sardinia, and it wasn’t always as easy as one might imagine. There’s a very powerful story that touches on this theme. It’s been forgotten by the collective memory of my village, but it’s worth telling.

A middle-aged man, apparently very lonely, lived on Via Garibaldi in Lodè. He had emigrated to Germany in the second half of the last century.

Germany is a deceptive land. People went there hoping to find something better, without really knowing what that “better” was. Often, they only found money. But money doesn’t fill the emptiness created by cultural distance.

And for those who weren’t used to expressing what they felt inside, the only way to survive was to build a small homeland far from home, closed off in tight communities, never really integrating (despite what people say, true integration is a very rare thing).

Leaving one’s homeland was extremely hard. A warm but desolate land, somewhere between Barbagia and Baronia, a place that, as Rosa Balistreri sang about her own Sicily, doesn’t hold you back if you want to leave, and gives you nothing to help you return.

But it’s exactly this indifference that creates a toxic bond.

As I was saying: this man returned to Lodè after a long absence.

Maybe he couldn’t wait to come back. Maybe he hoped to find what he had left behind: a place where he would feel welcomed, where no effort was needed to be understood, where he could pick life back up where he had left it.

But while the village had only changed on the surface during those years, he had changed deeply. And maybe he didn’t even realize it.

In small villages like mine, as years pass and the world moves on, there’s always a stagnant refusal to face differences. That same discomfort toward those who left and dared to see the world from another perspective.

That man couldn’t bear the most devastating kind of loneliness: the feeling of no longer having a place in the only world he had ever considered certain. In that place he called “home”, he felt like a stranger.

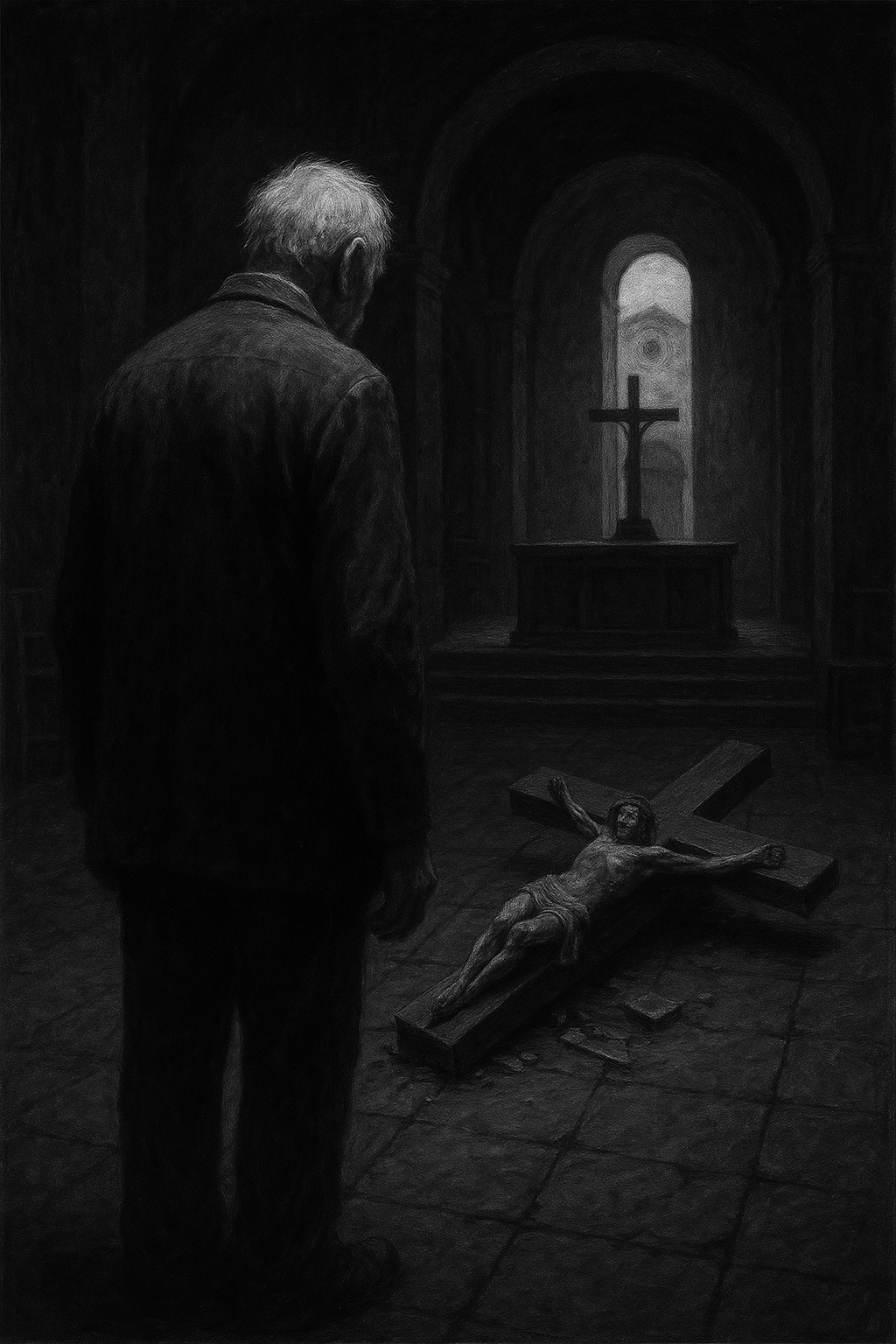

So one day he walked into the house of the Lord, the church of Saint Anthony of Padua.

While the priest was celebrating Mass as usual, he climbed the altar with determined steps and pushed over the three-meter-high crucifix. It crashed to the floor with a deafening noise that echoed through the church aisles for what felt like endless seconds.

That Christ, his face distorted by the nails and his bleeding side, lying on the floor among the shocked expressions of the faithful, seemed to suffer for him, as well as for himself.

The man died by suicide a short time later.

They found him dead in his house on Via Garibaldi. Since the adults couldn’t get in because everything was locked, they made a young boy climb in , a boy who, to this day, still lives with the memory of what he saw:

a man hanging by a rope, his teeth showing, his face bluish.

The sad truth is that, once you’ve left, you often can’t truly return.

Coming back isn’t enough to be welcomed again.

Speaking the same language doesn’t mean you’ll be understood.

Often, even the smallest change in you is enough to be rejected like a foreign body.

Because in places like these, everything can be forgiven, except change.

Because change, around here, always looks like betrayal.