“For this is the great error of our time… that doctors separate the soul from the body.” — Plato

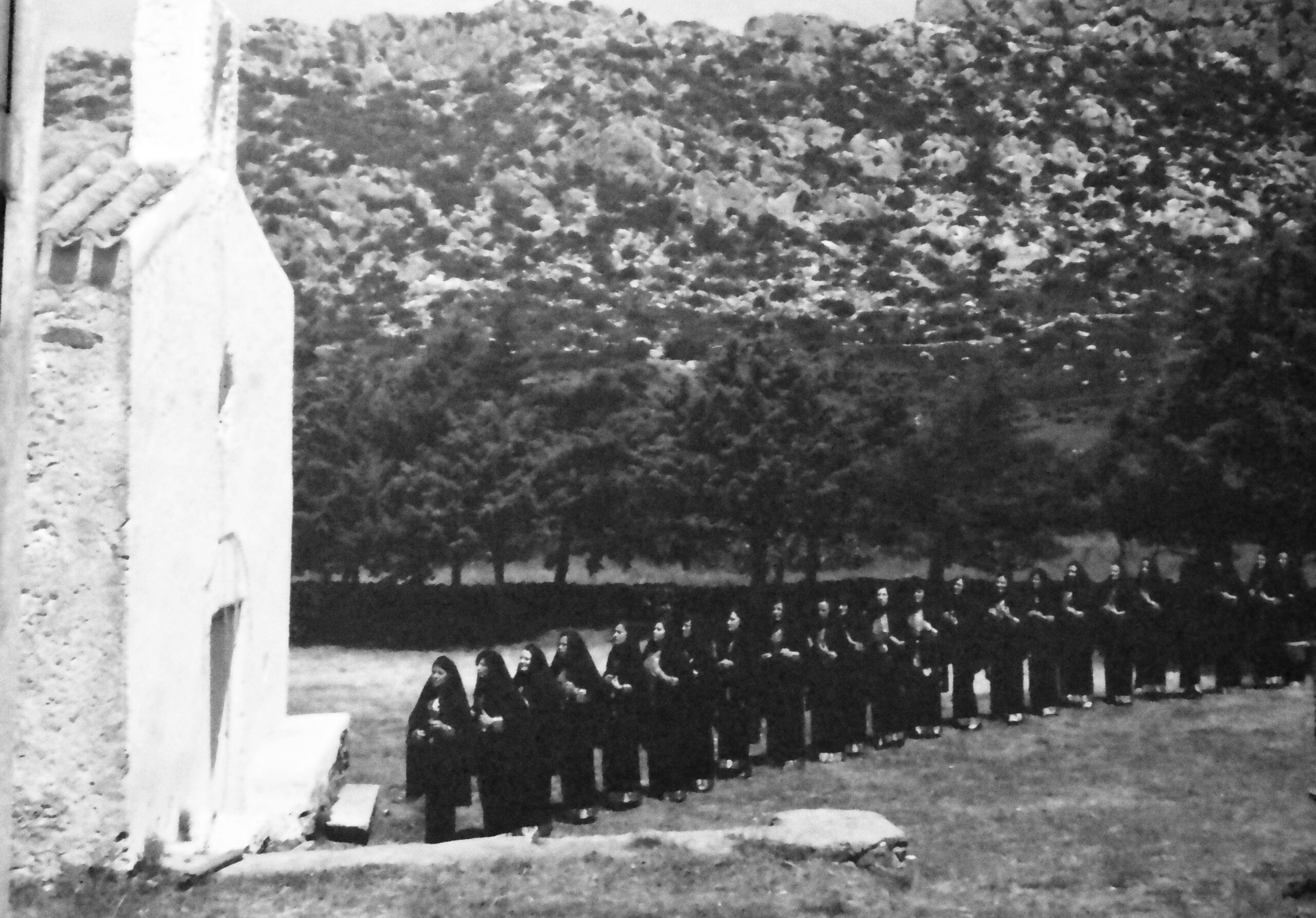

In Sardinia, there was a hidden group of women called “Deinas”, who did extraordinary things. Since there were no pharmacies to buy pills that could numb the pain without addressing its cause, it was up to the Deinas to cure the evil eye, the pains of the soul, and even those of the body.

The fact that they were women is no accident: they dominated this field (the male component was a minority), with a matriarchy that almost approached total supremacy because, in the ancient world, there was the idea that women, having a more intuitive and receptive connection to the world, acted as intermediaries between the visible world and the spiritual world, while men, historically, were always associated with a more rational and practical dimension of reality.

I never met them, but in Lodè, a small village in the middle of Sardinia, there are stories about Tzia Violanda and Tzia Battistina Chessa, two women who, using elements like fire, smoke, and herbs, practiced a form of benign witchcraft. A holistic way of taking care of a person’s ills, which had already anticipated the modern understanding of psychosomatic diseases, seeing the body and mind as an inseparable whole.

However, if you ask about the practices of these women in Lodè, people often fall into a state of aporia: in our anthropocentric age, dominated by rationality and arrogance, it becomes hard to understand how it was possible to believe in the soul and the invisible. Yet, the fact that these stories continue to be told suggests that perhaps these ancient practices were not all lies.

Precisely because the spiritual world has been downplayed in favor of science for centuries, only a scientist like Freud could make famous a practice that had already existed for millennia: the interpretation of dreams.

Among other things, the Deinas also did this (and they had been doing it long before the invention of psychoanalysis).

In Lodè, there were two ways of interacting with dreams: one passive and one active.

The passive one was called “Isteniare unu sonnu”, literally “to exhaust a dream,” and the Deinas did this not for themselves, but for others: so, people would go to them, tell their dream, and the Deinas would try to interpret what hidden meaning it might have. A Freudian psychoanalysis, archaic and free of charge.

But the active one, and in my opinion the more fascinating, was called “Orassione”, and as far as we know, Freud had no knowledge of it whatsoever.

A small aside: although today the term orassione has been Italianized and is associated with Christian prayer (orazione), in Sardinian pagan tradition, it didn’t have that meaning. It wasn’t a prayer to speak intimately with God, as the Italian term suggests, but a practice consisting of obsessively repeating a word or thought, with the intent of receiving answers that were not visible to our eyes but were revealed through what Freud later called the unconscious.

So, orassione, a practice almost entirely erased from memory, is not simply dream interpretation; it consists of thinking intensely and compulsively repeating something to obtain answers in dreams, but also during wakefulness, through signals called “assinzos”.

Practically, it worked like this: while systematically stringing the beads of a rosary between your hands, you would obsessively repeat, for days and in a low voice, an overwhelming thought or the name of a person, hoping that the answer to a question or the fate of that person would emerge through a dream or through sos assinzos. In this case, the dream would have a revelatory function: revealing what remained hidden to the eyes, what the unconscious had already understood and kept, like a secret hidden in the rooms of the soul—rooms inaccessible when the consciousness is awake. It’s important to understand the message behind this practice: the idea of the unknown parts of ourselves, meaning that we can’t access all parts of ourselves at every moment. This means that the reality we perceive doesn’t depend solely on us, because our senses deceive us. Subjectivity is limited. In this sense, the Deinas give us a great lesson in humility, which I believe is particularly necessary today.

The fact that the Deinas used a rosary during this practice, using dreams as a means of revelation not connected to God but to themselves, highlights another conflicting aspect of the island. This type of dream use is clearly in contrast to Christian faith, and it reveals, once again, how the Church sought to suppress and sometimes suffocate the most intimate and personal expressions of people. All attempts to uproot and oppress pagan roots have always met with resistance from the Sardinians, who still express their essence with an intimate rebellion.

In fact, when I asked my grandfather to explain what orassione was, he said it was just a prayer, but then he recited a poem that says:

“Muzzere mia, cando andat a missa,

achet Orassione a santu Leo.

Issa precat a minde morrer jeo e jeo

preco a sinde morrer issa”

My wife, when she goes to mass, does the prayer to Saint Leo.

She prays for me to die, and I pray for her to die.

Of course, asking a saint to make your spouse die is hardly orthodox. Yet, in Sardinia, in the most intimate rooms of the soul, being heretical is not considered a sin.