I visited an abandoned prison, and as often happens, places where past suffering still lingers shake the soul, at least a little.

Among all the photos I took there, one shows the small window of a cell: inside, it’s pitch dark; outside, there’s light.

That little window is really tiny, and I thought about what a prisoner sees of life from there. What does a person feel, even if they made a mistake, being deprived of freedom and seeing the world through that tiny square for years and years? The light of life outside, and the darkness of the death of freedom next to them, day after day.

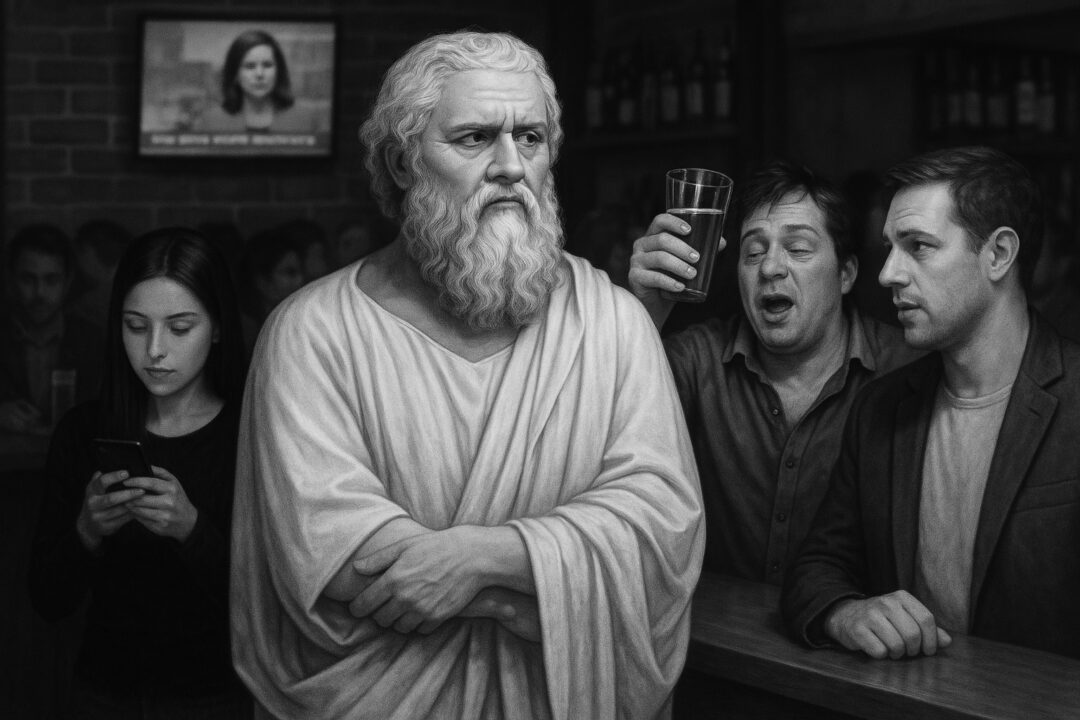

Prisons are a highly divisive topic. Common prejudices are always soaked in the desire to see those who have done wrong suffer excessively: “If they killed someone, they don’t deserve any pity,” or “Whoever does wrong must pay.” Others say, “They get food and shelter, and when they get out they even find a job!” And still others see the prisoner as a constant threat: “They’re dangerous to society.”

In extreme cases (rape, murder), this instinct is almost inevitable: it’s hard to imagine “accepting” someone who has committed such an atrocious act. And, honestly, it’s understandable, these are human arguments: if I imagine having to face a person who killed or raped my hypothetical daughter, I don’t know how I would react, I don’t know what judgments would come out of my mouth (and I hope I never find out).

However, there is a huge fallacy in these statements, driven more by a primal instinct than reason: a prisoner is a person, each with contradictions, fears, and the possibility of rebirth. But it’s only a possibility, and it must be nurtured, not because we all have to become Mother Teresa helping and forgiving everyone, but for practical reasons, because it benefits both the prisoner and society.

A prisoner who leaves jail after living in overcrowded cells that reek of urine, without contact with family or friends for years, perhaps beaten by other inmates, and many other harsh conditions, is not just a victim of the system: they risk becoming far more dangerous than someone who has had the chance to live decently, perhaps with psychological support and treated as a human being rather than as a beast. It’s a huge problem, because society itself creates the danger it fears.

The natural instinct to punish, though entirely understandable, doesn’t work. In Nordic countries, where prisoners are reeducated in prison and treated as civil human beings, with training and psychological support, recidivism drops. But better conditions inside prison are not a “magic wand”: the best results are achieved only if the social context upon release is favorable, when prisoners find work, social support, low inequality, etc. Punishing without reintegration only creates new criminals.

As always, the answer to such a complex question is far more complex than the question itself; but if we think about it for a moment, a solution exists, even if we refuse to accept it.

We should return to looking at reality from that little cell window and ask ourselves, as a society, whether we want to keep locking people in darkness or opening small windows of light.

Society is always a reflection of the fears and contradictions we refuse to see within ourselves, and perhaps, unconsciously, not accepting those who do wrong means we refuse to face the dark parts that are imprisoned within us.