One summer evening, during a family dinner on my grandmother’s terrace, we were chatting about anything and everything. As a good teenager, I was showcasing my talent for devouring everything on my plate. At that age, if nothing has gone terribly wrong, you find yourself in that glorious phase where rules are optional and, therefore, etiquette is an abstract concept. So, I shamelessly gobbled up every last French fry, not leaving a single one for my sister. She, glaring at me, didn’t lose her composure and pronounced, with the decadence of a nineteenth-century lady: “Sas pretas chi ti maniches!” – May you eat stones!

Before I even had time to process the curse, the sky darkened: first, a few drops, then a torrential downpour. A passerby, unfortunately without an umbrella, shouted: “Brocchettos de 30 chi proata!” – May 30-kilo blocks of concrete rain down! At that point, drenched and doubled over with laughter, we rushed inside while that summer rain continued to pour relentlessly.

To an outsider, such curses may seem like nothing more than crude obscenities, violating social taboos and propriety. But to a keen observer, they may reveal something more: tools of expression. Tools that expose tensions and, therefore, serve as a form of rebellion against external forces (in this case, the power of an unstoppable natural phenomenon, the rain, or the power of an insatiable teenage appetite).

Let’s start, as always, from the beginning.

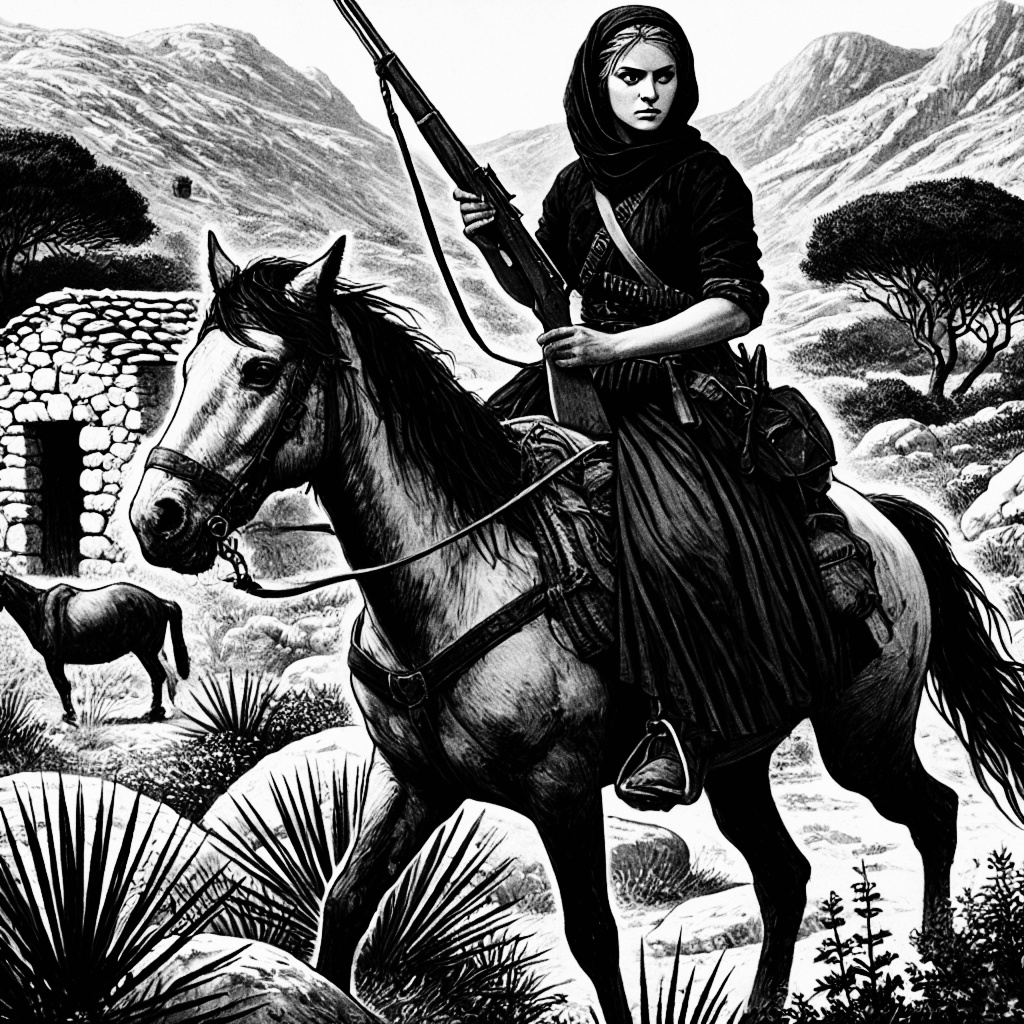

The Sardinian people are not a people who aspire to rule, but neither do they want to be ruled (at least, originally, they were like this). Becoming “izzu e babbu de isse mantessi” – son and father of oneself, is not just a common saying but a way of perceiving life: a kind of self-controlled anarchy where no one owns anyone, but each person is master of themselves.

Sadly, however, history books tell us that this innate characteristic of this people was never fully realized, but instead was constantly repressed by external forces. This is why Sardinians have developed a deep-seated distrust toward anything that comes from the ‘continent’ (in Sardinia, ‘continent’ refers to anything that is not Sardinia, including mainland Italy). Justice imposed from the outside has always been perceived as foreign, and this perception has historical roots. A fitting example is the Barbaricino Code: a set of internal laws within the island’s pastoral society that, once suppressed and dismantled by state justice imposed by the ‘continent,’ created a permanent instability that remains unresolved to this day on a sociological level.

Starting from this premise, I was struck by the intuition that this characteristic way of cursing developed as a symbolic response, a kind of revenge: all (and I mean all) Sardinians have cursed at least once in their life, whether against the law, the rain, the heat, bad luck, or someone who made them angry.

It is no coincidence that there are countless curses directed at Justice and the Law (where justice and law always refer to external authority, never internal community rules) or even fully formed rhyming maledictions:

“Zustissia ti brusiet, zustissia t’incantet. Zustissia bi colet e non lesset mancu chisina” – May Justice burn you, may Justice enchant you (i.e., make you dumb). May Justice pass and leave not even ashes.

State justice, the official justice of the government, is far more intimidating than divine justice in the eyes of a Sardinian, who perceives its language as completely alien. The Sardinian, watching bureaucracy unfold like a foreign film without subtitles, uses direct, visceral, unfiltered curses to reclaim an expressive freedom that neither the State nor any other authority can control.

So, to put it in psychoanalytic terms, cursing could represent the satisfaction of a repressed desire to reject external domination through the violation of a linguistic taboo that temporarily suspends the obligation of submission. A kind of liberation, a mechanism of release, used when one cannot act directly against a frustration.

Sardinian curses are often extremely vulgar or sacrilegious, and therefore break the rules imposed by society, temporarily transporting the speaker to an anarchic dimension. By expressing a ‘forbidden’ thought, one creates a liminal space, a temporary suspension of ordinary social structures, allowing deeper, more authentic impulses to emerge.

These curses haven’t remained limited to justice and misfortune but have also been used against people to express dissent, often with a mix of cruelty and irony.

So, if you leave a room without closing the door, someone might instinctively shout at you: “Sas manos che sa minca e nonnu” – May your hands become like my grandfather’s member (meaning, dry and lifeless, because he’s dead). Or if you laugh at someone else’s misfortune, you might hear: “Su risu e sa granata, chi s’est abberta e non s’est tancata” – May your mouth remain open (while laughing) like a pomegranate when it ripens (and therefore, never closes again).

But it’s best not to take it personally: it’s just a cultural metaphor, a tool through which a people vent their frustration for never having fully managed to govern themselves.