Not long ago I read an article in the Berliner Zeitung, which recounted an event that stirred significant indignation among readers: a man had killed two sheep inside his apartment in Berlin’s Köpenick district.

The man did something legally wrong: first, because he broke the law (it is not legal to slaughter animals in an unauthorized place); second, because, apparently, he had stolen the animals from a public park.

That said, for me it was inevitable to connect this news with personal and realistic memories and, from there, start a philosophical reflection… and ask lots of questions.

What really disturbs us in this story? The act itself? The location? Or the fact that it forces us to face something we prefer to ignore?

Let’s begin with a completely different reality. In a pastoral culture like that of Sardinia, killing an animal to eat it is not an act of barbarism. For example, my grandfather used to slaughter the lamb at Easter, and there was no dramatization, no particular cruelty: just an objective participation in lived reality. It happened that the lamb was brought alive behind the courtyard of the house and killed in front of us children, who, caught up in excitement, watched death up close, thus forming a somewhat more authentic relationship with reality, and therefore with life.

This anecdote will probably spark outrage in hundreds of people, but I believe very few among them would feel the same outrage in front of a supermarket meat counter, where tons of meat are stored and sold every month. Meat from animals that were surely treated far worse than how my grandfather treated his: free to graze outdoors, with few fences, food and shelter overlooking the sea, and even guard dogs to prevent unwanted encounters with people trying to steal them.

Behind this reflection lies a much deeper reality concerning us as human beings: namely, that we don’t want to see death, we don’t want to see the suffering that is part of life. We want it delegated, distant, clean, and we want to eat meat without knowing where it comes from.

In supermarkets, meat is cut, packaged, almost abstract. There is no blood, no eyes, no pain. But when we see blood up close, in everyday reality, it seems “inhuman” to us. In other words: the problem is not the act itself, but the fact that it happens right in front of our eyes.

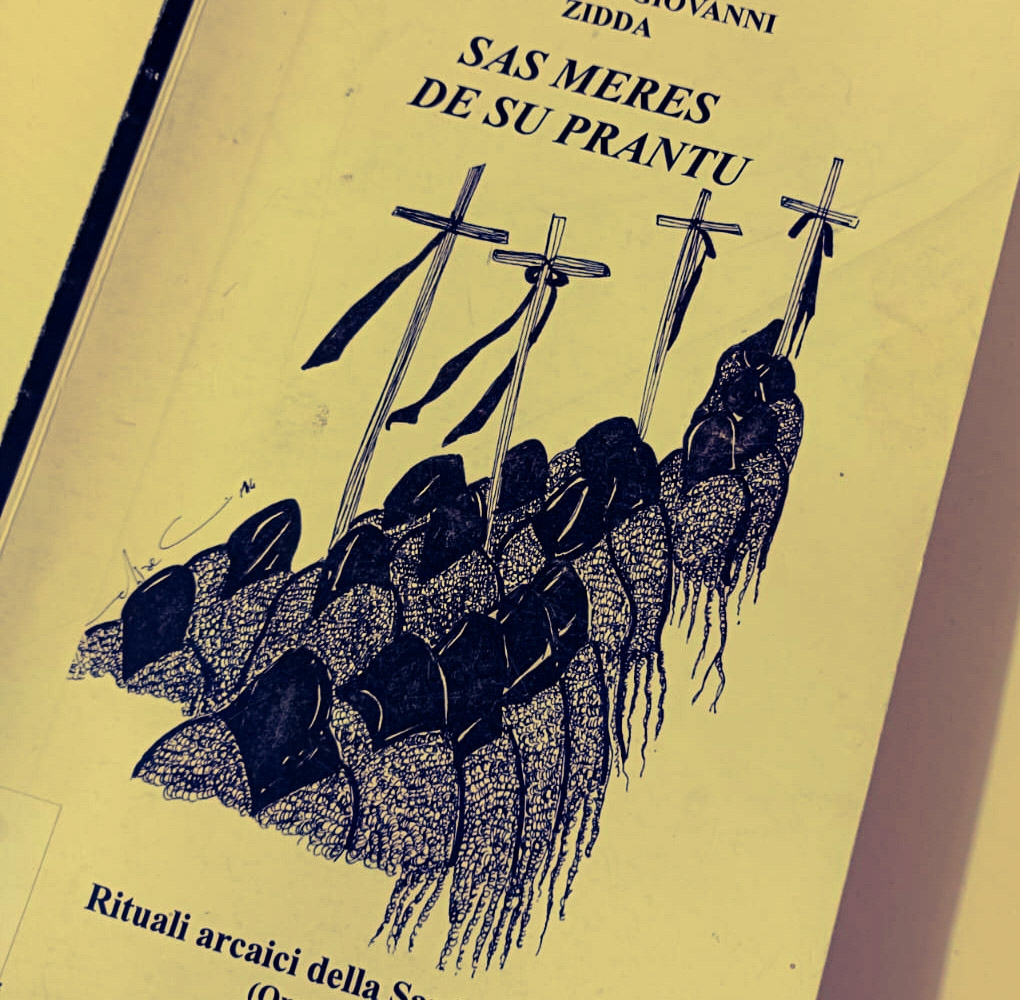

Human beings have always experienced sacrifice as a sacred act, not an industrial one. The culture of Sardinian shepherds is light years away from the cruel, capitalist logic of the meat industry.

Maybe we’ve lost touch with what real life is, and because of the widespread habit of seeing reality in black and white, we have lumped everything together without seeing the fundamental differences: we are unable to distinguish that someone who kills with respect is not necessarily cruel, but someone who consumes without thought and awareness certainly is.

For this reason, while respecting people’s personal choices and the noble attempt to avoid suffering any living being, we must admit that veganism is inherently contradictory, even though it presents itself as radical consistency. After all, like it or not, living means always entering relationships of exchange, and sometimes death is part of that exchange.

In other words, I have not yet met vegans who don’t own a smartphone. Yet every smartphone has a cruel impact on animal life, even if we don’t see it, because our phones contain metals like lithium, gold, copper, cobalt, and their extraction forces the total destruction of forests and the suffering and death of many animals. A suffering that goes far beyond the momentary one my grandfather caused to the lamb when he killed it for Easter lunch. Not to mention that many miners are children or exploited adults, without protections and in dangerous conditions.

Perhaps the real problem is not death itself, but how animals arrive at death. And maybe we should look more closely at the system that kills in silence every day, rather than getting outraged by a single episode that simply forces us to look. Because the real horror is probably not the death of animals but our desire to hide the suffering that is part of life.