April 1969: in Orgosolo, rumors spread that the area of Pratobello, used by shepherds to graze their flocks during the summer months, would have to be cleared to make way for a military firing range.

Only at the end of the following month was the news confirmed, as large posters appeared throughout the town. They informed the shepherds: Pratobello must be vacated. The State had decided that this communal pasture would become a firing range for the Italian Army’s training. The understandable distrust of the Sardinians towards state institutions exploded.

Not very cleverly, convinced they could deceive the people of Orgosolo, the State promised compensation of 30 lire per day for each sheep and claimed that the exercises would last only two months. Too bad that 30 lire was insufficient, considering that feed cost 75 lire per kilogram, and people suspected that the two months would turn into many more.

Indeed, the people of Orgosolo didn’t buy it at all and began organizing assemblies and peaceful warning demonstrations: just to make it clear to the Italian State that it’s rude to remember the Sardinians only when there’s an opportunity to exploit their land, as happened in Roman times.

They tried to reach a union agreement, without any result. When attempts were made to mediate with the State through diplomatic channels, the people of Orgosolo responded that “the battlefield for shepherds is not the parliament,” explaining in simple terms that the fight to defend Sardinian lands takes place on Sardinian soil, not in Rome.

Betraying (as always) the hypocritical phrase that “the State acts in the interest of the citizen,” the interests of the people of Orgosolo were completely ignored. On April 19 of that year, the first day scheduled for the exercises, the military headed towards Pratobello, but the exercises never began: a crowd of three thousand people, including men, women, and children, stood in an endless line of resistance. Everyone was there, not just the directly affected shepherds, but also students, workers, men and women, the very elderly: Dionigi Deledda writes in his book dedicated to this uprising that a former outlaw of almost a hundred years, Tziu Battista Corraine, known as “Zoeddu,” responded to the military’s request to step aside: “I’m almost a hundred years old, and if you harm me, I don’t know if you’ll live to be a hundred like me.”

In the following days, the people of Orgosolo found their path blocked by the armed forces, but they didn’t give up. Some got out of their vehicles and proceeded on foot; others even manually moved the military trucks. The people of Orgosolo occupied the area, and the army’s special forces deployed about four thousand men. Many arrests followed for resisting public officials. But the people didn’t yield: the struggle continued for almost a week, and even Emilio Lussu sent a message of solidarity to the people of Orgosolo, describing the State’s behavior as colonialist and stating that, if his health had allowed, he would have naturally participated in the struggle in person.

In the end, the people’s determination prevailed: the State confirmed that the firing range would be removed by mid-August and that any similar proposals in the future would be discussed with the local administration, in the interest of the local population.

And a people’s struggle like this, the oldest shepherds would say, they had never seen in their lives. All the progressive islanders, in solidarity and with great sympathy, shook hands with Orgosolo and said: this is true bravery.

E una lotta de populu gai,

naraìan sos bezzos pili canos,

chi in bida insoro non l’han bida mai.

Tottus sos progressistas isolanos

Solidales, cun tanta simpattia

A Orgosolo toccheddana sas manos

E naran: custa sì ch’est balentìa.1

Thus concludes the poem by Peppino Marotto dedicated to this victory.

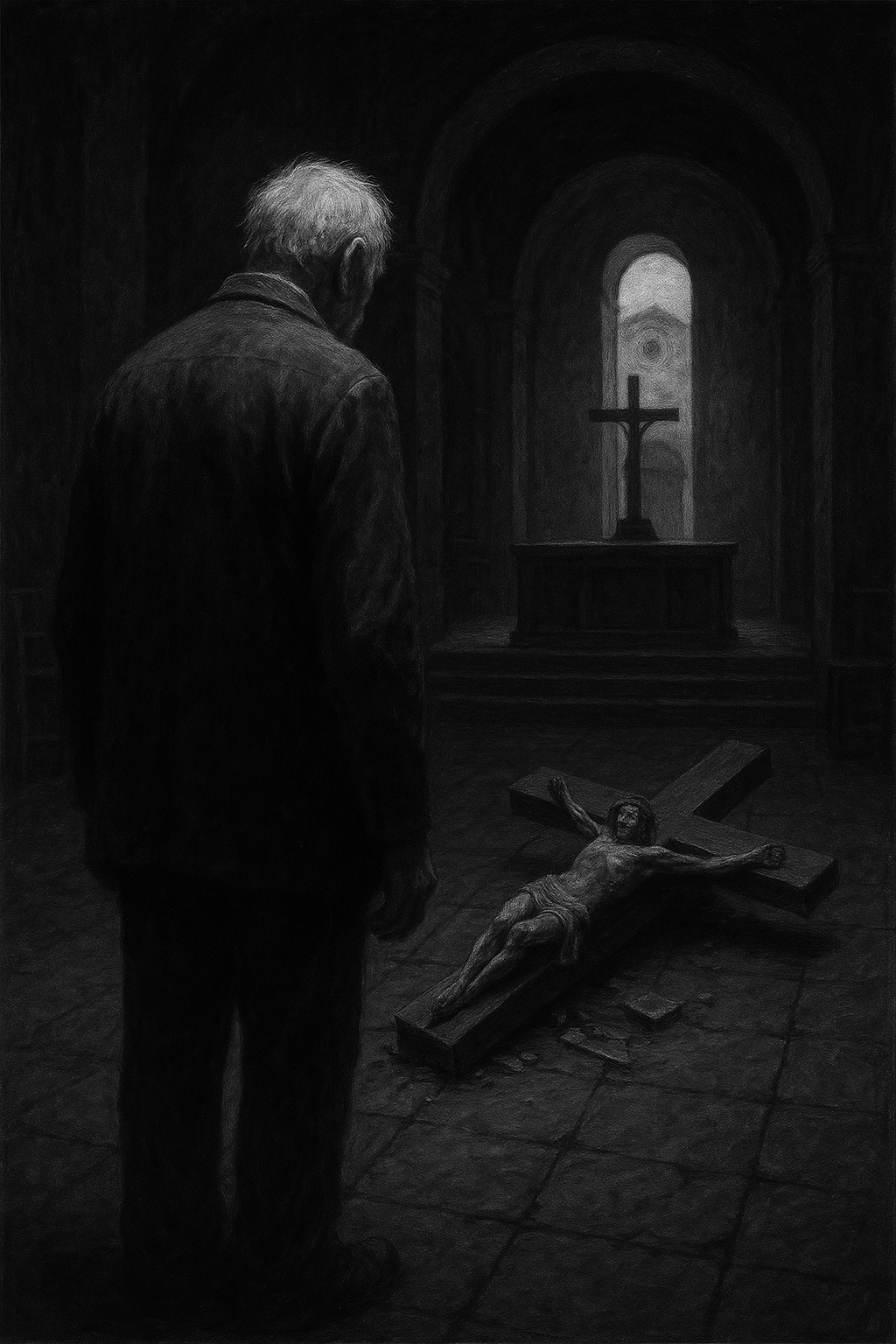

Today, Pratobello is empty, forgotten, immersed in a severe silence that seems to observe, motionless, all those lands in Sardinia ceded to NATO for firing ranges and more. Along with its silence, resistance, pride, and solidarity have fallen silent.