In a hospital room, a 98-year-old woman longs for human connection. She is objectively exhausting, she forgets things, she is half-deaf, so you have to repeat yourself multiple times. Her sentences are disconnected, and her requests objectively unnecessary.

A nurse enters the room once again, responding to her harshly, with a loud and irritated tone. The old woman falls silent, then complains loudly, frustrated.

This girl is very young, but she is definitely doing a job she doesn’t love, I thought.

Later, another nurse comes in to attach my IV and starts complaining, saying that she is tired, confused, and doesn’t really understand how to administer my medication. Alarmed, I say, “This morning, in the other ward, the doctor told me that this medication must be administered for a maximum of six hours.”

“I don’t know how long the infusion should last,” she replies, completely ignoring what I just told her.

Later still, as dinner is being distributed, another nurse, clearly unmotivated, shuffling his slippers noisily down the hallway, says to me:

“Miss, we don’t have your meal because the other ward didn’t enter you into the system. Do you want a salad?”

Already irritated by the chaos I had been thrown into, I snapped back that he could eat that salad himself and that I wanted my proper meal.

He ignored me, placing the salad on my bedside table along with two slices of bread salvaged from someone who didn’t want them.

My infusion lasted 11 hours (this morning, the doctor confirmed it should have been only 6), and I ended up buying food from a vending machine because the salad filled my stomach as much as a marble would fill a cathedral.

Being a nurse is an incredibly delicate job. You deal with people who are suffering, people whose pain should first be eased by human warmth before by opioids. People who are there because, in that place, they have placed a hope: the hope of not being treated as numbers but as human beings.

So, before learning how to draw blood, a nurse should first learn what empathy is.

Just as a doctor should learn it before forgetting that the Cartesian separation between mind and body does not exist in practice, even though most doctors persist in categorizing people as a collection of organs whose functionality depends solely on mathematical operations.

A postal worker should learn it before snapping at an old lady who is just trying to understand the new technological systems that have invaded her savings.

A teacher should learn it before forgetting that they hold one of the most important and impactful jobs in the world, repeating soulless lessons like a nursery rhyme while their students yawn, praying to some random god for them to shut up as soon as possible.

James Hillman said that each of us has a specific calling in life: our task is to find it and fulfill it.

When someone does what they were born to do, work becomes a form of self-expression and a service to others.

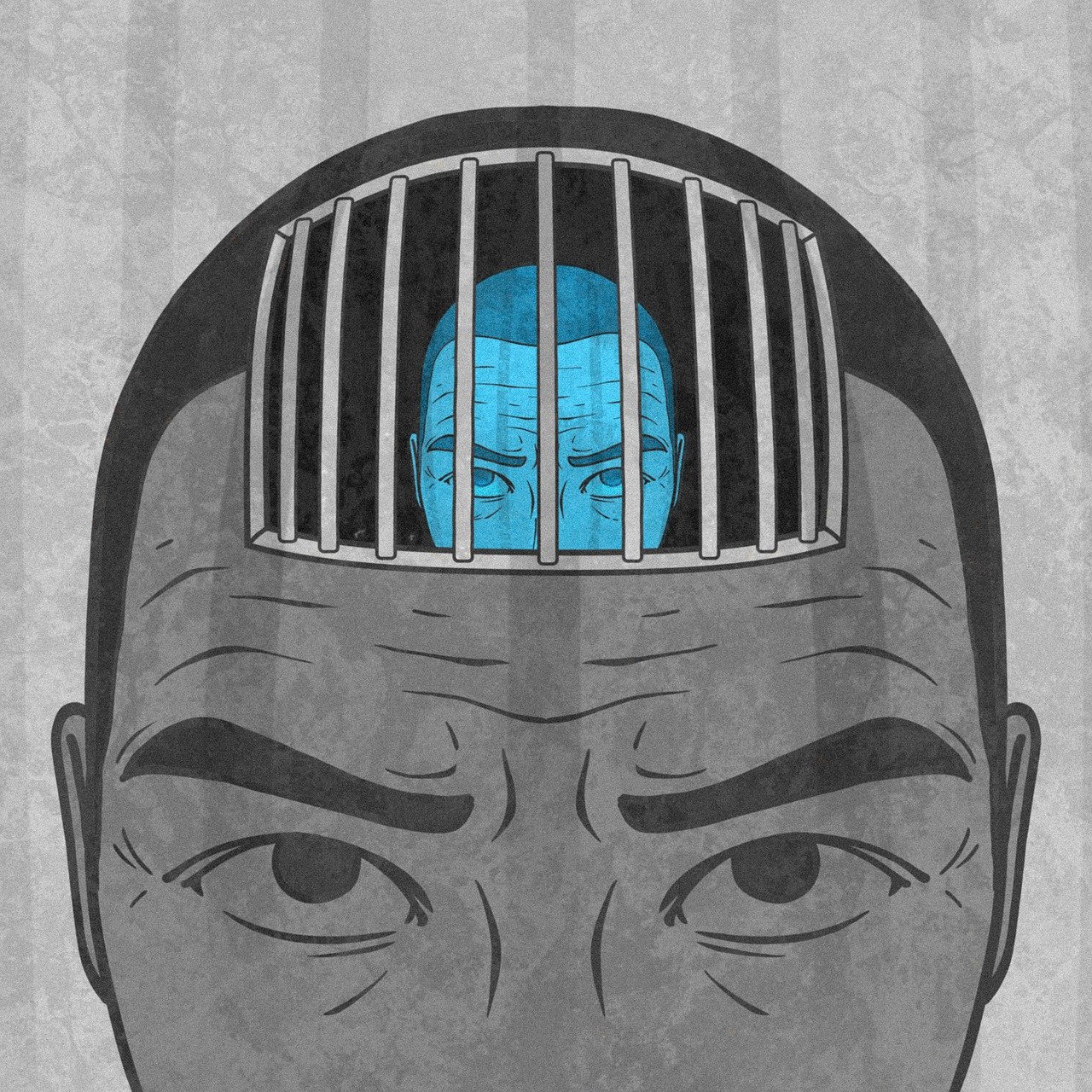

But generally, the exact opposite happens. Work is just a way to get a paycheck, and people choose security over fulfillment.

The most common path is: school → university → stable job → retirement.

The result? We are surrounded by frustrated nurses with no empathy, drained teachers, employees embittered at the world.

When we go to a restaurant, we deal with rude waiters. Offices overflow with bureaucrats incapable of smiling, supermarkets are full of cashiers whose mere presence makes you feel hopeless, and public transport drivers wear boredom on their faces like a mask.

Yes, I know. It’s not always possible to do a job you love passionately. But that doesn’t justify becoming a social cancer, spreading misery to everything and everyone you come into contact with.

It’s up to us to find a way to express ourselves elsewhere.