Walking through a small town in Sardinia also means being watched. It’s not uncommon to realize, just when you think you’re invisible on a nearly deserted street, that an old lady is peeking out from her window or that the elderly man, seemingly unaware of your presence, is actually tracking your movements with the corner of his eye while chatting with his hands clasped behind his back.

This is often perceived as an annoyance, especially by younger generations, who have never really come to terms with the myth of personal freedom. The very same young people who complain about being spied on by the village old lady and claim they have no privacy, post their entire lives on social media, making themselves dependent on the very thing they resent: what others think of them. The problem is that this sacrifice of privacy no longer serves the practical function it once had in community-based societies; now, it is purely about appearances.

But why is curiosity about others so deeply rooted in Sardinian villages (and elsewhere)? I’m not talking about curiosity driven by envy, but rather the kind that seeks to understand others, to assess who you’re dealing with, and ultimately, to keep them in check (let me explain what I mean).

Although this kind of intrusion can often feel irritating, there is a specific reason why monitoring others’ behavior is an essential part of the unwritten rules of traditional societies.

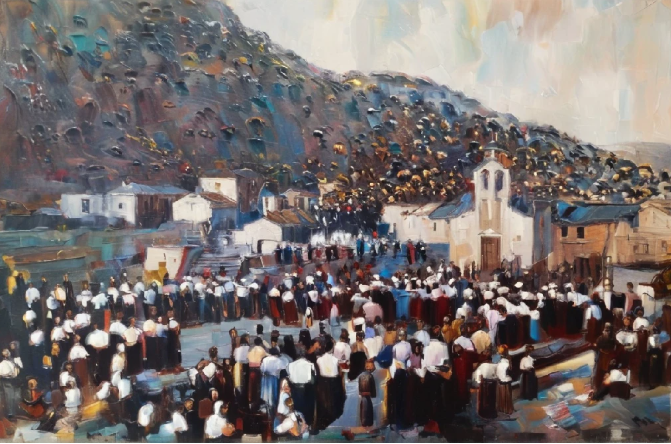

In concrete terms, before selfishness rebranded itself as individualism to gain legitimacy, in traditional and community-based societies like Sardinia, the individual was less important than the community. A person, when taken alone, has the potential for complete freedom, but within a tightly-knit community, they must abide by specific rules, and therefore, they are monitored. Control is fundamental to preventing the social fabric from weakening. A community like Sardinia’s could not afford to be weak, especially given the enormous collective challenges it faced in the absence of efficient official regulations.

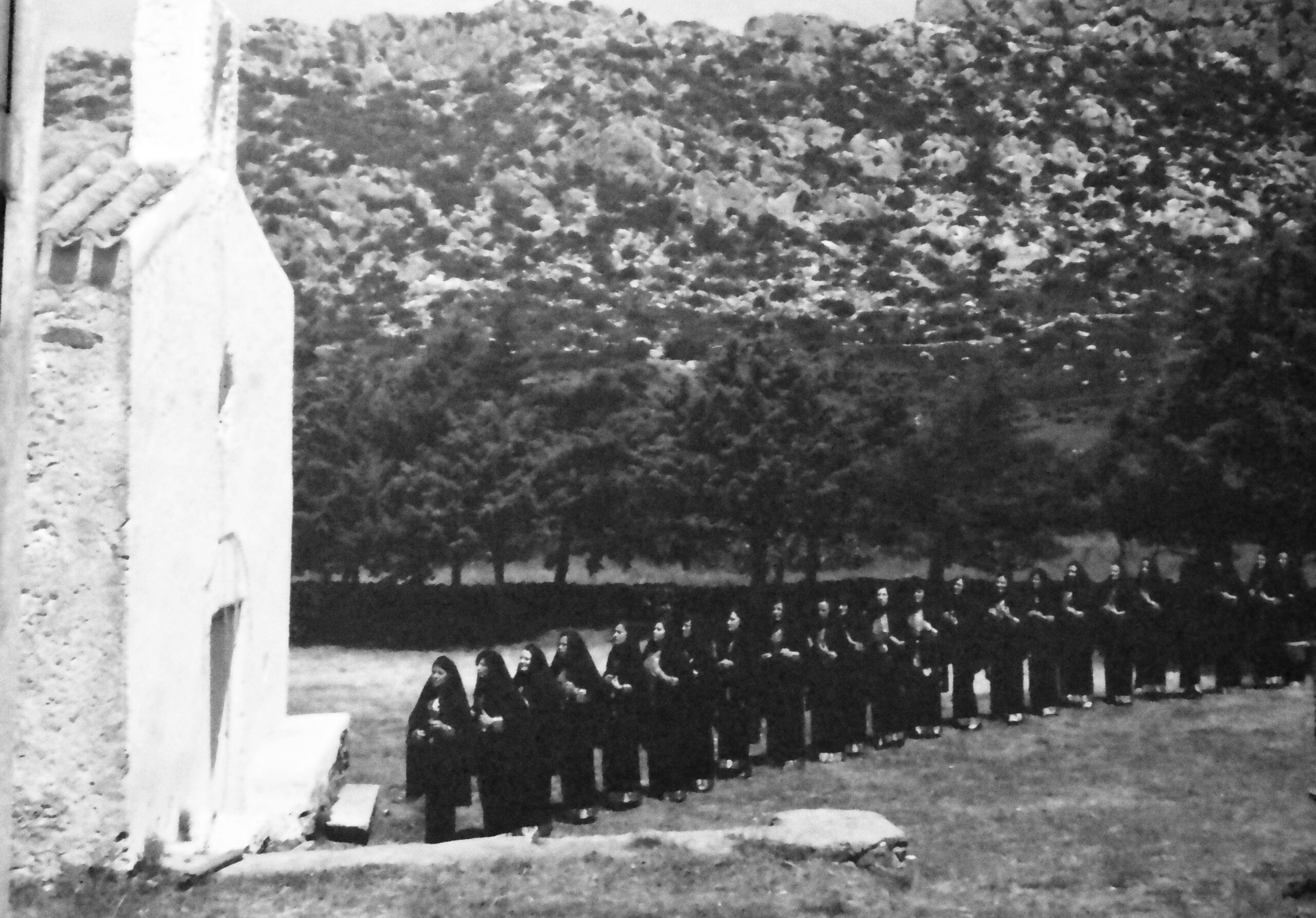

This form of control was exercised informally, through shared but unwritten social norms, public opinion, and gossip. In practice, everyone was subject to an unspoken obligation to behave in a certain way. A system that monitors people’s behavior, personified by the old lady watching from behind the corner with her sharp eyes, makes individual’s actions predictable. This is because anyone who knows they are being watched adjusts their behavior accordingly, whereas in the absence of watchful eyes, they may act entirely differently (no one talks to themselves in public, but everyone does when they’re alone).

Those who deviated from social norms in a Sardinian village risked being marginalized and, as a result, no longer felt part of a society they fundamentally needed. It is necessity that fosters cohesion and altruism. It is no coincidence that today, in the absence of real necessity, individuals are far more self-centered and perceive themselves as superior to the community.

The fear of deviating from social expectations or being excluded creates a strong bond between individuals. Of course, this can feel suffocating for those who seek to assert themselves as individuals. But, as always, gaining something means giving up something else.

The real conflict lies in sacrificing a significant portion of one’s personal freedom to entrust it to a community that both protects and constrains at the same time.

Perhaps the depopulation of Sardinian villages is, in part, influenced by this intrusion, which, no longer justified by any real necessity, has become an end in itself. Unlike in the past, the community now offers less protection, and as a result, it risks becoming self-destructive.